drawing from life (DFL)

the illustrator's ULTIMATE research tool

|

In my role as Senior Lecturer and Programme Leader for Illustration at the University of Cumbria, I believe that drawing fundamentally underpins illustration. Is this a particularly unusual ethos? One hopes not, yet the exploration of drawing practises and the nurturing of core drawing skills within illustration courses at the Higher Education level is seemingly considered less crucial as once was.

With advancements in digital media, there are those who argue that drawing has become redundant and is no longer central to development as an illustrator. I wholeheartedly disagree. Indeed, when asked to review a newly published ‘how to become an illustrator' guide, I was alarmed to read its opening salvo which stated that due to digital media usage and increasingly diverse styles of illustration, an ability to draw was no longer important in the world of illustration. In my opinion that's exactly the wrong advice to provide for students and early-stage practitioners, and indeed this theory is undermined by clear evidence to the contrary. By bypassing research drawing processes, we side-step a crucial strengthening component of the illustration toolkit or skill set. We must consider the creative process as a whole, starting with research and investigation that provides the understanding which in turn is utilised in exploration and experimentation, before ideas are developed towards the production of final outcomes. With this holistic viewpoint, the significance and importance of drawing is undeniable. In a 2021 interview with the Guardian, Peter Blake lamented the decline of drawing classes in art education, noting that: (drawing) "is still there, but it moves in and out of sight”… it is my feeling that as educators we have a responsibility to respond robustly to this apparent diminishment – encouraging the embedding of drawing – underscoring it as a ‘protected characteristic’, fundamental to the language of the illustrator. At the University of Cumbria, the craft of drawing is woven throughout our illustration programme, with a core tenet that by regularly drawing from life (DFL), our students develop creative abilities, awareness and comprehension developed through regular drawing practise. On a surface level, DFL is the simple the act of exploring and capturing physical environments, forms and objects in space, but beneath this lies a deeper, rich layer to unfold and examine. DFL is an often complex and challenging task that promotes deeper levels of understanding - coordinating and synchronising the brain, hand, and eye. <Something about studies into drawing as a tool for learning/memory> “When we draw, we encode the memory in a very rich way, layering together the visual memory of the image, the kinesthetic memory of our hand drawing the image, and the semantic memory that is invoked when we engage in meaning-making…. Drawing forces students to grapple with what they’re learning and reconstruct it in a way that makes sense to them.” – Youki Terada, ‘The Science of Drawing & Memory’, George Lucas Educational Foundation. The DFL process is one of constant observation, judgement, adjustment, and consideration – the development of new understandings through active learning. It includes all manner of processes that can be deployed within the context of illustration, including composition, contrast, mark-making, use of colour, perspective, narrative, proportion, and use of media. DFL is an often ignored or overlooked research tool for the illustrator which, using Frayling's framework, is best understood within this context as research THROUGH illustration (though can also be considered as research FOR illustration when utilised to develop a specific brief*). Illustration students at the University of Cumbria exploring Jill Calder's many research sketchbooks (above) which underpin her work on Robert the Bruce (below)

|

Scratch the surface of 'Drawing from Life' and what do we find?

Observation Looking at and visually exploring the world around us provides a greater sense of human understanding and an awareness of the subtleties of life required to humanise or anchor an artwork. The recognition, interpretation and communication of significant details is an important skill for any illustrator. Perspective A convincing use of perspective drawing techniques as well as an understanding of how perspective works in terms of a 2D image, can be the difference between a flimsy work and a potent and believable one - regardless of 'style'. Too often naive styles are adopted in order to avoid these 'difficult to master' ideas. We want our students' visual language to be the result of development and choice rather than necessity. Anatomy It's likely that an illustrator will have to work with human anatomy on a regular basis - often using its manipulation as a means of communication. I like to term observing and drawing the human figure from life as 'wild life drawing'. Technique & Media Research THROUGH illustration in a very pure sense. It's crucial that central to a student's development is their ownership of a toolkit of materials and approaches which will play a key role in defining their visual language. DFL plays a large part in allowing them to practice these materials and approaches. |

EXAMPLE - CHRIS WARE

|

Renowned American artist and graphic novelist, Chris Ware, exemplifies the use of DFL (Drawing From Life) as a valuable research tool in artistic endeavors. His published sketchbooks, known as The Acme Novelty Datebook: Sketches and Diary pages in Facsimile, Vol 1 & 2, provide important insights into how DFL influences an artist's work. Ware's DFL sketches, which differ significantly from his well-known illustrative style, showcase a deep exploration of everyday American life - from homes and decor to clothing and cars. While these sketches may not directly impact his final artwork in terms of aesthetic or technical aspects, they serve as a foundation for the narratives in his graphic novels, which often center around the lives of ordinary people. By studying the visual language of the world around him through DFL, Ware gains a deeper understanding of the nuances that shape his storytelling. As a result, we often refer to Ware in discussions about the meaningful role of DFL in the artistic research and development process.

|

Chris Ware sketchbook (top and left) and page from his 2019 graphic novel, 'Rusty Brown' (bottom). The visual languages of both of these pieces of work could not be further apart, despite being from the same artist and, broadly speaking, dealing with similar subject matter. The research sketchbook work inarguably underpins and informs the outcome.

|

MY OWN DRAWING FROM LIFE JOURNEY

Over the past 15 years, I have dedicated a significant amount of my commuting time to creating illustrations of my fellow passengers while traveling on the X95 cross-border bus route from Langholm to Carlisle. This activity has evolved from a casual way to pass the time, alongside activities such as reading and scrolling through social media, to a focused practice that influences my current interests and research in reportage illustration and drawing.

Despite obtaining my driver's license a year ago, I choose to continue commuting on the bus in order to gather more 'bus drawings' and further develop my skills in this area. In 2018, I completed a Master of Arts in Creative Practice, using my 'bus drawings' as the foundation for exploring reportage illustration. This marked a deliberate shift away from my previous approach to illustration, which had been primarily digital with elements of traditional drawing. I felt disconnected from this style and sought a more authentic voice in my work.

This transition, coupled with my teaching position, allowed me to pivot towards a more meaningful direction in my artistic practice. What began as a casual hobby has now evolved into a long-term research project, unintentionally shaping the development of my work and artistic process through my 'bus drawings.'

Over the past 15 years, I have dedicated a significant amount of my commuting time to creating illustrations of my fellow passengers while traveling on the X95 cross-border bus route from Langholm to Carlisle. This activity has evolved from a casual way to pass the time, alongside activities such as reading and scrolling through social media, to a focused practice that influences my current interests and research in reportage illustration and drawing.

Despite obtaining my driver's license a year ago, I choose to continue commuting on the bus in order to gather more 'bus drawings' and further develop my skills in this area. In 2018, I completed a Master of Arts in Creative Practice, using my 'bus drawings' as the foundation for exploring reportage illustration. This marked a deliberate shift away from my previous approach to illustration, which had been primarily digital with elements of traditional drawing. I felt disconnected from this style and sought a more authentic voice in my work.

This transition, coupled with my teaching position, allowed me to pivot towards a more meaningful direction in my artistic practice. What began as a casual hobby has now evolved into a long-term research project, unintentionally shaping the development of my work and artistic process through my 'bus drawings.'

EDITORIAL WORK (PRE 2016)

|

Examples of professional illustration work.

The technique shown here, for which I gained some reputation as an editorial illustrator, is perhaps best described as digital collage utilising primarily hand drawn elements as well as various found images, textures etc. The major underpinning inspiration for this work was mid-century American illustrators and their use of photo-mechanical reproduction as well as texture, gesture and colour. Left: Wired Magazine UK Top right: for Creative Review Bottom right: for Cycle Active magazine |

MA WORK (2016-2018)

DEVELOPMENTS IN MY OWN WORK

SETTING A START POINT (2012-2013)

SETTING A START POINT (2012-2013)

|

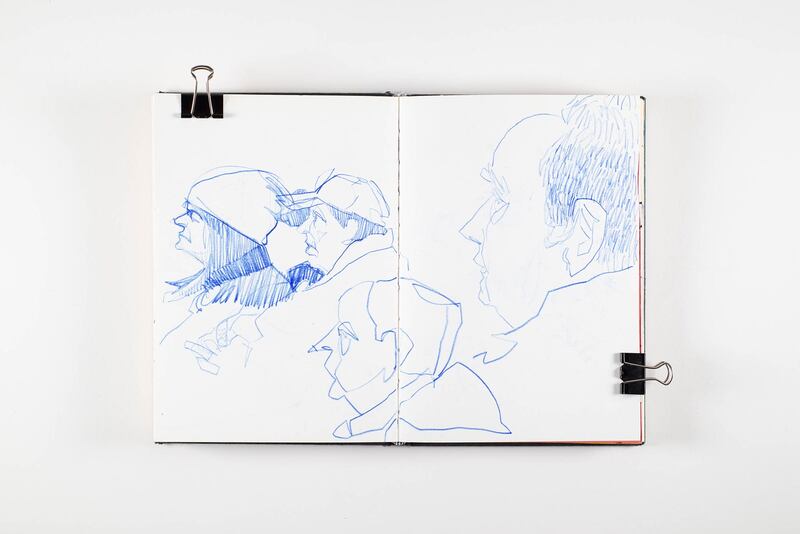

In order to chart the developments that I have made through my 'bus drawing' practice, we must go back to early sketchbook pages and identify the beginning of my drawing on the bus on a regular basis. Whilst it would be possible to identify bus drawings from the late 90's, when I first started keeping a sketchbook, these would be one-offs and therefor I don't consider them to be part of the ongoing endeavour that I'm examining here.

Reflecting on sketchbooks amassed over the last 10+ years, it's abundantly clear that DFL and specifically drawing on my commute, has provided me with considerable development in terms of the quality and confidence of my drawing as well as the use of materials/media. In its truest sense, this is research through drawing. Some of the developments are subliminal or accidental, the product of repetition. Others are intentional and a result of my conscious efforts to take my work in particular directions - often influenced by the work of other artists, contemporary or otherwise, working in a reportage or adjacent field. Early bus drawing examples are, upon reflection, often inconsistent and suggest an underdeveloped ability to capture anatomy or body language. My use of materials is best described as being in an exploratory stage where I'm giving everything 'a go' but often without clear intent. This is not a criticism of my own work, after all, this freedom is exactly what a sketchbook for, however, it does provide a base from which to judge development/growth/change. |

(Above)

Bus Drawing from 2012/2013 (sketchbook undated). At this time I was using a breadth of drawing materials ranging from pen, brush and ink, coloured pencils and, as here, chinagraph. I had, for some years and through much exploration, already settled on A5 portrait sketchbooks as the only option I would consider. This example is a Daler Rowney Ebony. This was a period of exploration and discovery and what the work lacks in consideration and clear intention it gains in freedom and risk taking. |

|

(Left)

Bus Drawings from 2012-13 (sketchbook undated) Early drawings were focussed on the bust and rarely showed anything below the torso. I remember struggling to successfully compose the image within the A5 page or combined A4 spread. This would be among the first challenges I set myself to overcome. Another early realisation was with regard to showing aspects of an environment, in this case a bus, in order to place my subjects in a believable or relatable space. Without some amount of contextual detail to ground the subject, the drawing's looked like what they were - exercises, but with the introduction of some amount of those details , an aspect of narrative became evident. The drawings presented themselves as more than the result of a drawing exercise (though we can see, on the left, that these realisations have not yet been addressed). |

DRAWING ON A MOVING BUS

|

In conversation, as here, it's very easy to overlook the inherent difficulty of drawing whilst onboard a moving vehicle. It's the type of realisation that really presents itself when encountered first hand. Not only is the bus in constant motion, the road surface uneven (to say the least), but space is also cramped - the seat in front is only inches ahead and, depending on the side of the bus you're sitting on or if you've had to share a seat, at least one arm is pressed against either the side of the bus or a passenger (worst case scenario, both!). Add to that limitations provided by heavy coats in winter, bags etc, and it's difficult to label a commuter bus as anything other than a terrible place to draw. I have always attempted to make my bus drawing activities as clandestine as I possibly can and this adds another level of difficulty.

First instincts are to fight the motion, to somehow try to work around it and counter it in the lines or marks made in the act of drawing. This is, of course, a fool's errand and what I learned was to accept the motion into the drawing, to allow it to influence and inform the outcome. In the same way that a drawing created en plain air, in the rain would be expected to look 'wet', a drawing created on a cramped and moving bus should be expected to reflect and be informed by those limitations - which turns them from limitations into contributing features of interest.

In the early stages of my bus drawing endeavours, I made other notable discoveries and adopted certain useful practices pertaining to the logistics and realities of drawing on a bus. For example, it became an unconscious norm for me, when boarding the bus, to use the small pause provided by buying a ticket, to scope out the passengers already seated. Here I was looking for both an interesting or suitable subject* and an available seat (on the driver's side if possible, as I'm left handed and this means my drawing hand won't be pressed against the outer wall of the bus). The two things rarely present together and the decision of where to sit and who to draw has to be made quickly - and of course is then dependent on other people not getting in the way. All of this to say that all attempts at control are often for nought.

*Old people are interesting to draw, as are people with interesting features - a hat, beard, arm in a cast. Bags, rucksacks or big coats offer interesting visual components to wrestle with. |

Sketchbook October 2014

One of the first adaptations to my approach was the development of a stark line that moved quickly and harshly from anchor point to anchor point. This was my attempt to work around the movement of the bus. The pen would cling to a fixed point whilst I made a decision regarding the next stretch of line and then quickly moved the pen from anchor-point A to anchor-point B, producing this staccato line which often, depending on media and paper quality, would include small ink blooms at the anchor points showing the my hesitations. |

DISCOVERY OF THE LAMY FOUNTAIN PEN

NOTATIONS

DISTORTED FREEDOM V LITERAL CONSTRAINT

INSTAGRAM & COMMUNITY

WATERCOLOUR

HATCHING

iPAD & PROCREATE

|

These three images (left) were all drawn on the iPad using procreate.

Dating from 2014 these were created shortly after taking ownership of an iPad for the first time and represent a conscious effort to learn and familiarise myself with both the software and hardware. We had noticed iPads being used by a small number of students and realised we would need to keep up. Now, almost 10 years later, the iPad and Procreate are almost as ubiquitous as photoshop or illustrator. For 1 month I drew only on the iPad in order to fast track my learning and gain a practical understanding that would allow me to help students with the technology. Despite being digital, these are still 'drawing from life' and as legitimate as any analogue version. 'Drawing' and 'digital' are not mutually exclusive. (embedded from instagram as I'm unable to locate the original digital files) |

ON THE X95 VOLUMES 1 - 4

Site powered by Weebly. Managed by 34SP.com